2000-2005

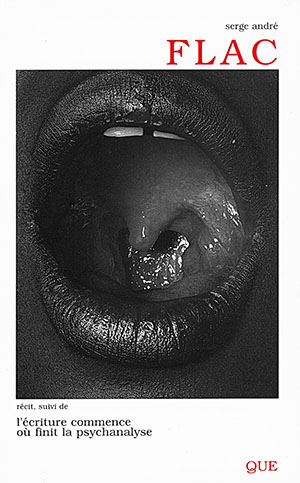

At the origin of all my work is FLAC, a novel by psychoanalyst Serge André

THE BOTTOM OF THINGS

“So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it.”

Georgia O’Keefe

In certain Japanese clubs, one can observe a new type of striptease. Women spread their sexual organs directly in front of the oculist witnesses who question the origin of the world. It is all about going deeper than the intra-utero, back in time, to forget the longing.

Photography is a silent and solitary ecstasy. It is the illusion of observing elsewhere what has already been seen. How can we focus on sex after Mapplethorpe, Warhol, Toscani and so many others.

Given the waterfall and the illuminating gas, how can one explore the lost continent in a new way.

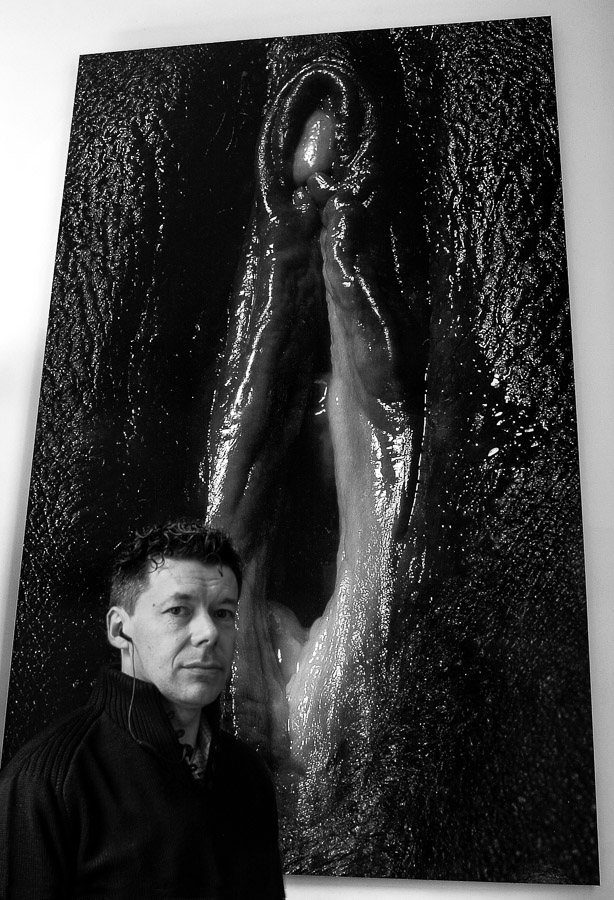

De Cugnac, while looking closer, curiously originates a certain distance. Giant prints transform us into Lilliputian astronauts, luring us towards what we believe we have already seen.

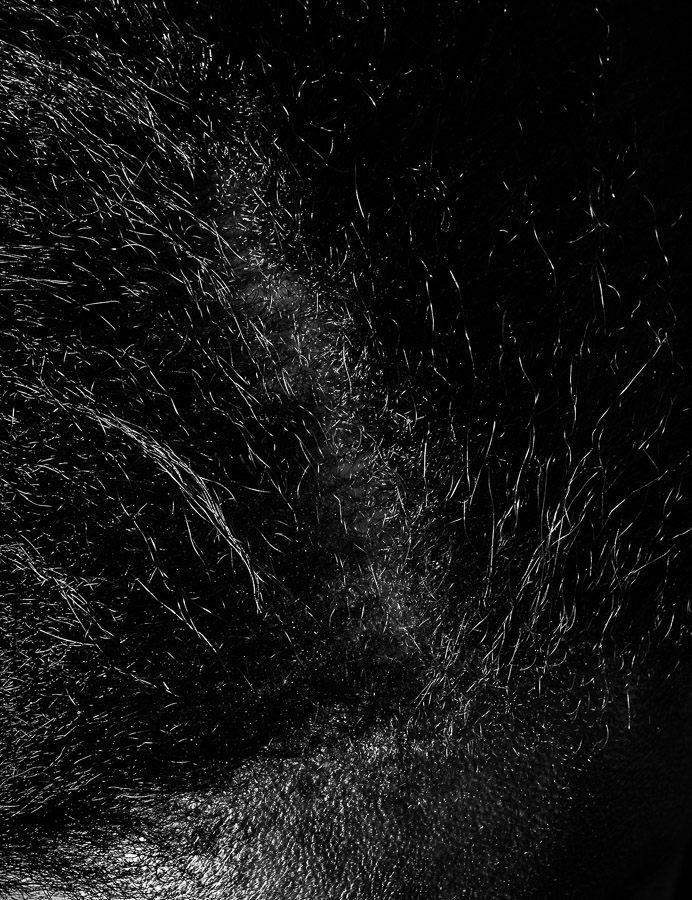

As a result, the enigmatic centre becomes a crater, an abyss, a geyser, a slit, surrounded by a desert of black skin scattered with swampy reeds.

Fig, mussel, oyster, fake scar, the indefinable frontier between the inside and the outside are underlined through aesthetic references.

Black, darkness, funereal, drastically icy, with implicit traces of Soulages, Degottex, Fontana. This Zen sobriety filters our perception and depornographises our observation, sending us into a cosmic dream.

Astonishment and fascination for the cavernous, the obsolescence of the ultimate revelation that can only lead to nothingness. Such is the mirror that de Cugnac offers us from the depths of his dark room while he hopelessly seeks to get to the “bottom of things”.

Dothy Soliman, Sept. 2002

Translated by Jordan Greenwood

DETAILS AND THE REST

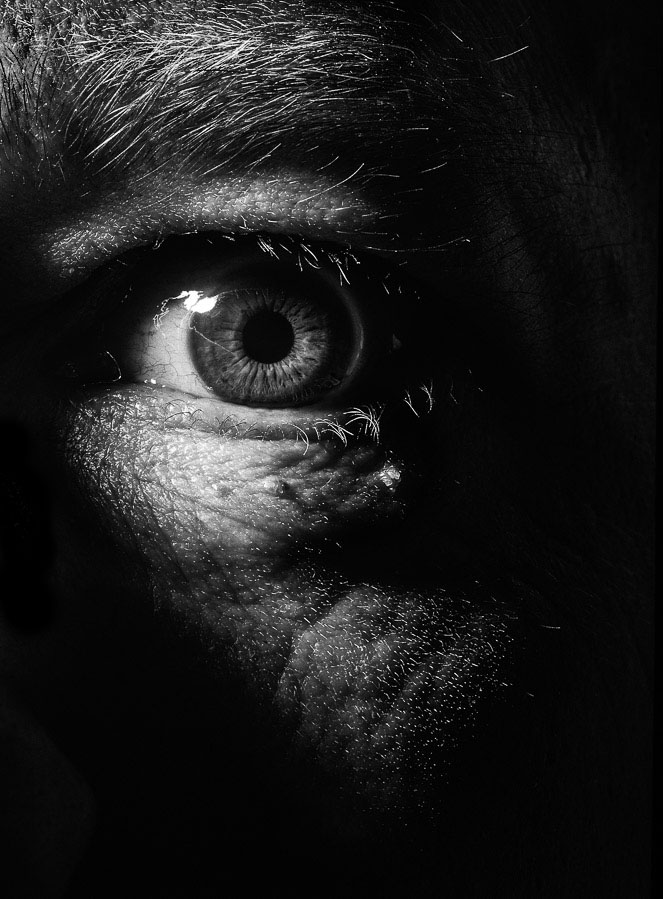

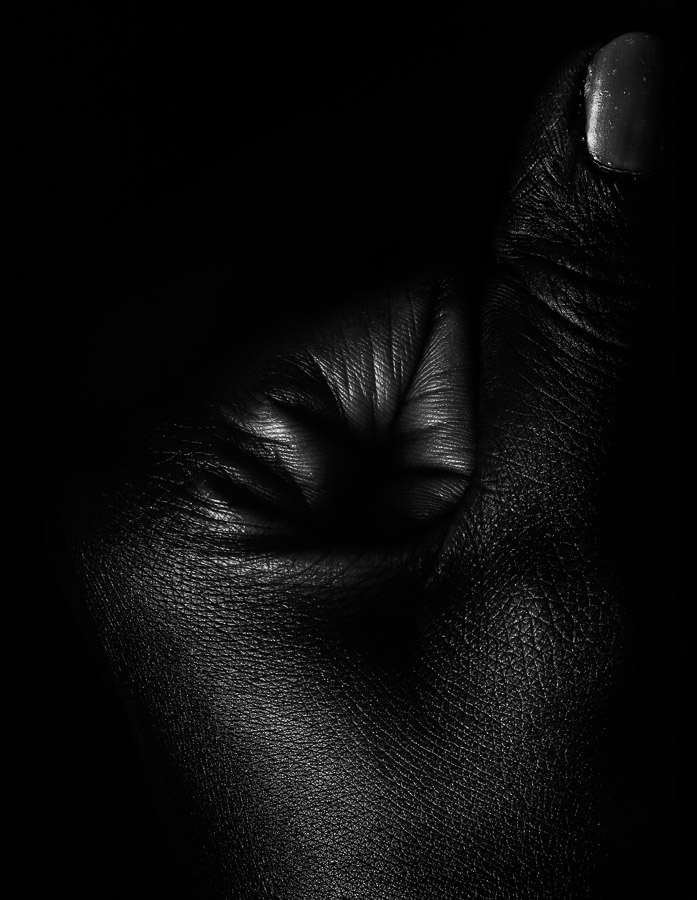

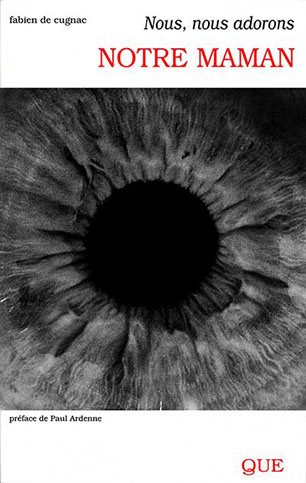

If, as Aby Warburg used to say, God is in the details, then Fabien de Cugnac is surely a visionary, a genuine religious fanatic for God’s works. What details is he fond of? Those of the human body, and he gets so close to the subject’s body that his lens acts like a magnifier. Mouths, eyes, women’s or men’s genitals (some with hair, some without), ears and skin, these are the details that this precise photographer picks out from the rest of the body. And he treats them after the manner of the post-Renaissance ‘blazon’ poets, concentrating so much on a single detail so that it becomes not just metonymic but truly emblematic.

Fabien de Cugnac composes these pictures meticulously, always starting from total darkness and gradually adding light, clearly aiming for an image that is both aesthetic and clinical. An image, moreover, that lets us see as clearly as possible, beyond the unnoticed – the inside of a vulva, the shape of a clitoris, the texture of a tongue peeping out between the twin fleshy line of the lips, the complex lines of an external ear, the precise distribution of hairs on the skin’s surface – he achieves maximum visibility by exploiting light to the full.

The use of black and white only, the very high definition and the constant search for contrast give these pictures an abstract quality. For all that, de Cugnac is undeniably in favour of incarnation, of physicality. In these photographs the eyes have a liquid surface; the vulvas may hold urine in droplets or spurt it out; tongues glisten with saliva. The body is seen both as an object of fascination and as an expression of life.

So the attention to detail is not indiscriminate: the subjects of these photographs tend to be zones of interchange in the body, where something passes through, in transition, or comes out. Fabien de Cugnac seems to remind us that seeing and admiring beautiful pictures of ourselves is not the whole story. We also need to accept the body as a vessel with various substances in occupation or residence, not just a picture but also an organ. The body depicted by de Cugnac is something alive, something fully involved in the action and processes of life (one series shows the bellies of pregnant women). In this respect the body is a dual entity. Like Lacan’s ‘partial object’, it connotes the opposing principles of wholeness and separation, in a constant a tug-of-war. At first sight the detail in the photograph brings to mind the totality, the whole body.

But the totality, in this case, is absent, kept out of the picture. As with Magritte’s five-panel female nude Eternal Evidence, where each superimposed canvas shows a different part of the body, de Cugnac’s photos show each part of the body in its place, we could even say its proper place: life is present in each, the parts get a life of their own because, in effect, the rest of the body is left out or negated. We hardly need reminding that – in the history of photography – close-ups have often been schizophrenic in this sense (witness John Coplans’ pictures of his own aging body). The subject is captured, admittedly, but is unable to recognize the self in the photograph: in other words, one has the painful experience of not always being able to recognize oneself.

Does this make Fabien de Cugnac a schizoid photographer, a clever manipulator concealing his split personality behind a screen of impeccable technique and finish? There could be a grain of truth in it, but this theory is weakened and transcended by the power of the work itself.

Opting to put ‘fragments’ first is this artist’s way of saying that his life involves a fascination with out-of-the-way corners and inaccessible areas, the body taken apart as a way of protecting his own self; and to saying that in such places he finds extraordinary beauty, unusual effects and a potent aesthetic. Is it ultimately a way of giving value to the rest, to what is lacking in these close-ups, the total image of ourselves?

This is highly unlikely. Yet some representation of ourselves does seem possible, if only on condition that the wonderful and ever intriguing icons of Fabien de Cugnac perform in their ambivalent fashion. The artist allows himself to ignore what he prefers not to show in the image, what is in fact impossible to show, the world itself, beyond our means. Photography as an existential tactic, conclusively.

Paul ARDENNE, PhD in Arrt History, 2004

Transalted by Michael Novy