2018-2024

The unbearable insignificance of self-centered art

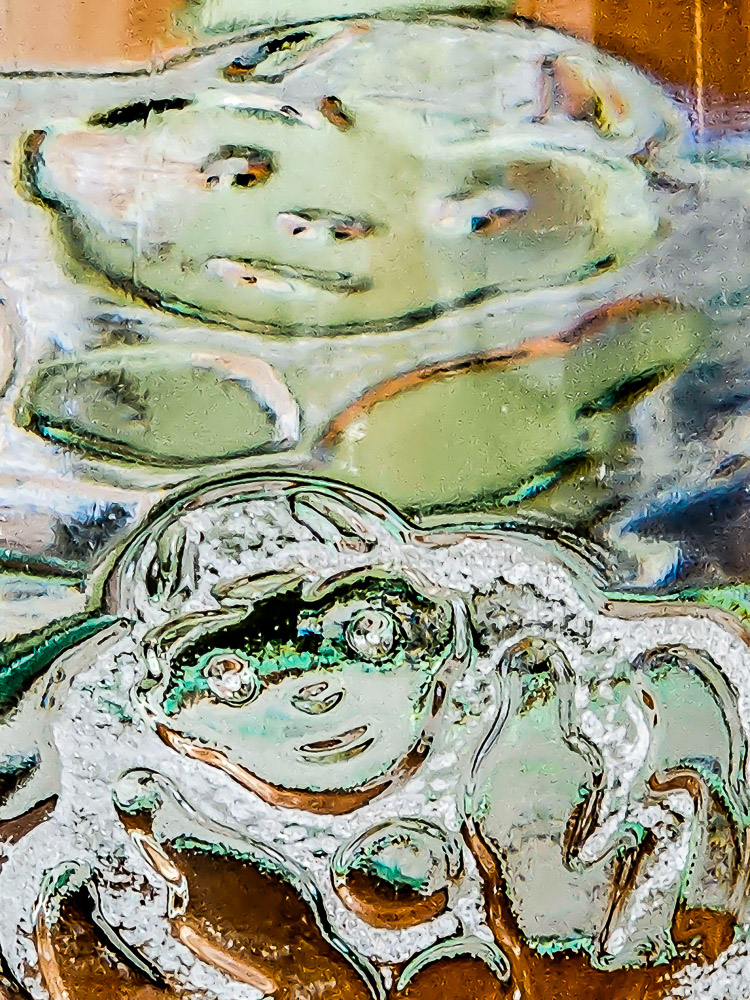

The Impossible Question of the Selfie

Given any passport photo – the zero degree of self-portraiture – if anything is to be said about it, an ocean of possibilities opens up, and the critic finds himself, like Siggi, the character in Siegfried Lenz’s German Lesson, punished for not having been able to write a single line of an essay on “the sense of duty” (before isolating himself to write a novel). You can say anything about a selfie, but where do you start?

A brief history of the selfie tells us what we already know: we can easily imagine the first self-portrait, which is, by the way, the subject of a historical dispute that we don’t care about. You don’t need to have studied the early days of photography to get an idea of the daguerreotypes of vain bourgeois. The democratization of photography has left us with lots of portraits of smart guys in front of their mirrors, and with contemporary art, there is no end to the great names who have used them, from Man Ray to Warhol, via Cindy Sherman or Ai Wei Wei. And then came the smartphone, social networks and those who are said to influence us.

What could have pushed Fabien de Cugnac to build a work around the selfie? We can’t imagine a stern voice, dead or alive, popping into his mind, as in Alain Bashung’s song Samuel Hall, and telling him “You’re going to produce something that works, my friend! It’s not the house style.

The following could be a theory in the same way that a tree in flower or a spider are self-portraits. This theoretical proposition would lean more towards fiction, so it will not be discussed or defended in the pages of a specialist magazine.

The multiplication of talents and creative techniques means that when they meet the market, or even just the eye, the latter already expects something, which is the same as what it has begun to see. Let’s take for example a painter’s studio visited for the first time: one looks at a first painting, then at another that seems to be from the same series, and at a third that doesn’t resemble any of the two previous ones, and there is the first shock for the viewer. Fifteen, twenty, forty paintings, some in the same “style”, others not, compositions, colours, formats, still lifes, surrealist, abstract, humorous, melancholic, hard, trashy, figurative, as can be the work of a painter who has not been identified solely by a success or a way of doing things repeated identically. And here comes the criticism, finally: “Is it coherent?

There is a parallel to be drawn with coherence in production, with the scripts of commissioned films, which has to do with the recipe.

Now, if there is a facetiousness and a genius of the selfie that defies the public’s expectations, this is where it lies: presenting a series of selfies escapes the criticism of incoherence – since you are told that it is him, each time – and opens all the doors, gives rise to all the narratives, evokes all the moods, suggests other attitudes each time.

One can certainly try to tell a story from an artist’s video that doesn’t tell a story, add phylacteries to Hopper’s paintings or make a statue belch a slogan, but what Fabien de Cugnac’s selfies succeed in doing is creating a desire for literature that is not a recipe, with words that don’t follow a pattern. And yet, everything that can make a story is there: the disturbing strangeness, the joyful pop of a music video, the intrigue: “but where is he in the picture?”, the effect (“but where is he in the picture?”), the nature, the insect, the animal, the plastic, the sky and the temperature, the part of the body, naked, clothed, alien, father, miniature and even sympathetic. Nothing is the same. Everything is consistent. You have recognized it.

Bruno Wajskop 2022